Virtual Reality: The Unknown Unknowns

by Calvin Armstrong

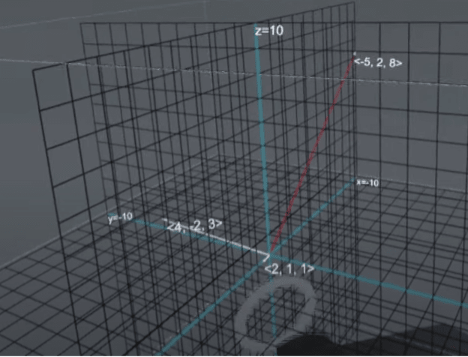

Technology has taken a long time catching up with my imagination. I can recall vividly as a high school student trying to construct a physical 3-d representation of vectors (roughly, arrows that float in space and interact with other vectors and objects) as I tried to describe and expand on what happened when they were added, subtracted or multiplied together and how they could be used to construct other objects as a result. Well, that collapsed in a misery of dowels, string and fishing line. The physical space just wasn’t up to the challenge.

But now, we have spaces that extend beyond, or perhaps, side-by-side with, the physical space. Using a Meta Quest Virtual Reality (VR) headset, we can superimpose a virtual collection of objects that float in the space before us, and we can interact with them with our hands. My goal is to translate my incipient physical model from decades ago into the virtual space.

Using a Meta Quest Virtual Reality (VR) headset, we can superimpose a virtual collection of objects that float in the space before us, and we can interact with them with our hands.

The first step has been to learn how to program content for a VR headset. To say it is object-oriented programming is to make a rather obvious joke – each object you bring into the space (be it dot, line or box) is brought to life based on its interaction with and/or proximity to other objects. You’re not really telling the objects what will happen as in a play’s script – rather, you’re training them how to react when something happens. It is like improv acting where you just give the actors an idea and they run with it, you’re never quite sure it’s going to go as planned. As a mathematician, comfortable, nay, secure with the logical, structured, algorithmic, one-step-follows-the-other to a pre-determined conclusion, the sense of letting these objects do as they feel is unsettling, even though I have set their conditioned responses myself. The learning curve has been steep, but enjoyable even when disastrous. Having your “world” collapse literally in front of your eyes gives one a greater sympathy for the Almighty.

And, as with anything on a knowledge frontier, there are things you know you don’t know, and things you don’t even know you’re unaware of. Fortunately, during the past twenty-odd summers, I’ve been working with participants at the Park City Mathematics Institute on topics in advanced mathematics and education. Serendipitously this past summer, Carol Dalrymple, an Emmy-award winning documentary filmmaker, ran a workshop on creating VR materials. Now, while her work is predominately researching, interviewing and filming for later presentation in VR, the discussion I had with her about my project brought an artist’s approach to what I saw as a (cough) simple mathematical problem. She reminded me that VR is a “space” and as such, I was focused so much on the visual of drawing geometric objects that I was ignoring the other sense that VR encompasses – the audio. And it is not just “sound” – audio in VR is 3-dimensional as well. It is sound that can emerge from, or directed to, a location. An additional aspect of the project has expanded to how one uses sound to not only gain the user’s attention, which is trivial, but how to direct them to where they may be missing the importance of the interaction of the vectors, or to assist them in ensuring they’ve aligned or located the vectors correctly. And it brings to a question how we use sound in the classroom (the real, physical one) - again, not just to focus attention, but how can we use it to add to the meaning and understanding of the content at hand.

It’s a good reminder that we all struggle with this when we try, earnestly, to learn something outside our present knowledge set.

As a veteran educator, I have regularly tried to find occasions to return to student-hood outside of my comfort zone, and this grant has enabled that, even though I am working on a mathematical topic that is rather elementary. The frustration, the impatience, and the sense of wonder – just as I experience it, our students encounter them as well when they engage with their unknowns. It’s a good reminder that we all struggle with this when we try, earnestly, to learn something outside our present knowledge set.